FRAME WATCH: Framing the Impressionists, part 2

Posted: 15 Jan 2018 by PML

The framing experiments of the young Impressionists (see Framing the Impressionists: Part 1) were not very long-lasting (save for those of Degas and Pissarro). Their painting style was fresh and radical, and - marketed with faith and persistence by the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, and commissioned by a few perceptive patrons - their work gradually gained traction in the art market during the last third of the 19th century. However, the collectors who bought Impressionist paintings were, as previously noted, to a great extent American merchant princes with recent fortunes, who wished to furnish their grand, newly-constructed mansions with contemporary art as well as with Old Masters. These modern works had to fit into revival Renaissance, Baroque or Rococo interiors, and the plain, geometric frame profiles favoured by the artists, finished with polished white gesso or painted in colours complementary to the paintings, did not fit into the interiors of the Gilded Age.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Sleeping girl with cat, 1880, in French Louis XIV frame; Sterling & Francine Clark Art Institute

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Sleeping girl with cat, 1880, in French Louis XIV frame; Sterling & Francine Clark Art Institute

This explains the high number of Impressionist paintings which have come down to us in French Baroque frames of the late 17th and the 18th century, chosen by dealers to suit the taste of their clients (a good collection of such frames, finely carved and opulently finished, can be seen in the Sterling & Francine Clark Art Institute, as described in Part 1

Camille-Léopold Cabaillot-Lassalle (1839-88), Le Salon de 1874, 81.5 x 100 cm., Christie's, 21 January 2009

Camille-Léopold Cabaillot-Lassalle (1839-88), Le Salon de 1874, 81.5 x 100 cm., Christie's, 21 January 2009

However, it is also true that as soon as artists such as Renoir and Monet became fairly well-established, they abandoned the economical but less saleable white and coloured frames of their early careers, and returned to using more conventional gilded patterns. Camille Lasalle's painting of the Paris Salon was executed in the same year as the first Impressionist exhibition took place, and shows the type of frame which was expected in academic circles; these were revival NeoClassical in style, wide, richly decorated with applied plaster ornament, and furnished with stepped friezes or inlays at the sight edge.

Camille Lasalle, Le salon de 1874, detail

Camille Lasalle, Le salon de 1874, detail

Some of them have acanthus in the scotia or hollow of the frame, and some have fluting (above); some have small runs of architectural ornament, and there are varying numbers and areas of plain frieze; however, all those shown by Lasalle have, without exception, a garland of bay leaves running round the top edge or outer contour.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Chrysanthèmes, 1878, 54.3 x 65.2 cm., Musée d'Orsay

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Chrysanthèmes, 1878, 54.3 x 65.2 cm., Musée d'Orsay

An example of this type of 'Salon' frame with an acanthus hollow can be seen on Monet's Chrysanthèmes in the Musée d'Orsay; it has a very good provenance, having been acquired from the artist in the December of the year he painted it by Dr Gachet, familiar to us from his having treated Van Gogh in his final weeks. Gachet may have accepted it in payment for medical treatment of Monet; it remained in his possession, passing to his son who gave the whole collection to the state in 1951. This means that the Chrysanthèmes is almost certainly still in the original frame given it by Dr Gachet. It is a fitting border for the painting, with its wide bevel at the sight edge, linear rows of ornament reflecting the marble shelf beneath the flowers, and the shallow repeated motifs echoing the brushstrokes.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), La route de Versailles, Louveciennes, 1872, 59.8 x 73.5 cm., Musée d'Orsay

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), La route de Versailles, Louveciennes, 1872, 59.8 x 73.5 cm., Musée d'Orsay

Another version of the frame, this time with a fluted hollow, and also belonging to Dr Gachet's collection, contains Pissarro's Route de Louveciennes. It is very unlikely that either of these paintings would have been framed in this way by artists who were not very prosperous during the 1870s, and much more probable that it was the patron who was responsible. Both forms of the 'Salon' frame suit the paintings they contain, the fluted version emphasizing even more the sharp recession of Pissarro's townscape. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise (The Rowers' Lunch), 1875, o/c, 55 x 65.9 cm. (21 5/8 x 25 15/16 ins), The Art Institute of Chicago

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise (The Rowers' Lunch), 1875, o/c, 55 x 65.9 cm. (21 5/8 x 25 15/16 ins), The Art Institute of Chicago

Evidence such as this is vital when museums or private collectors need to reframe an Impressionist picture; for example, Renoir's Rowers' lunch at the Art Institute of Chicago, which dates, like the Monet and Pissarro above, from the 1870s, was reframed by Paul Mitchell Ltd in an enriched version of the fluted 'Salon' frame on Pissarro's Route de Louveciennes. The cabled guilloche-&-husk which replaces the fluting became popular with the advent of NeoClassicism in the 1760s, when it would have been carved into the frame. This plaster version is refined and subtle - it echoes the diagonal trellis with its scattered flowers, reinforces the spatial recession in the painting, and chimes with the graphic, feathery brushwork.

We know that artists such as Manet had tried to make their work acceptable to the spectators frequenting the Salons (and to the hanging committees who chose the pictures) by using these so-called 'Salon' frames (see Manet's Olympia, 1863, in Part 1). These were the kind of patterns the Impressionists were accustomed to seeing on the work of academic artists, and the kind that they abandoned for a brief period during their efforts to establish themselves. After the first few years of experimenting with coloured and white frames, however, most of them went back to variations on these traditional styles.

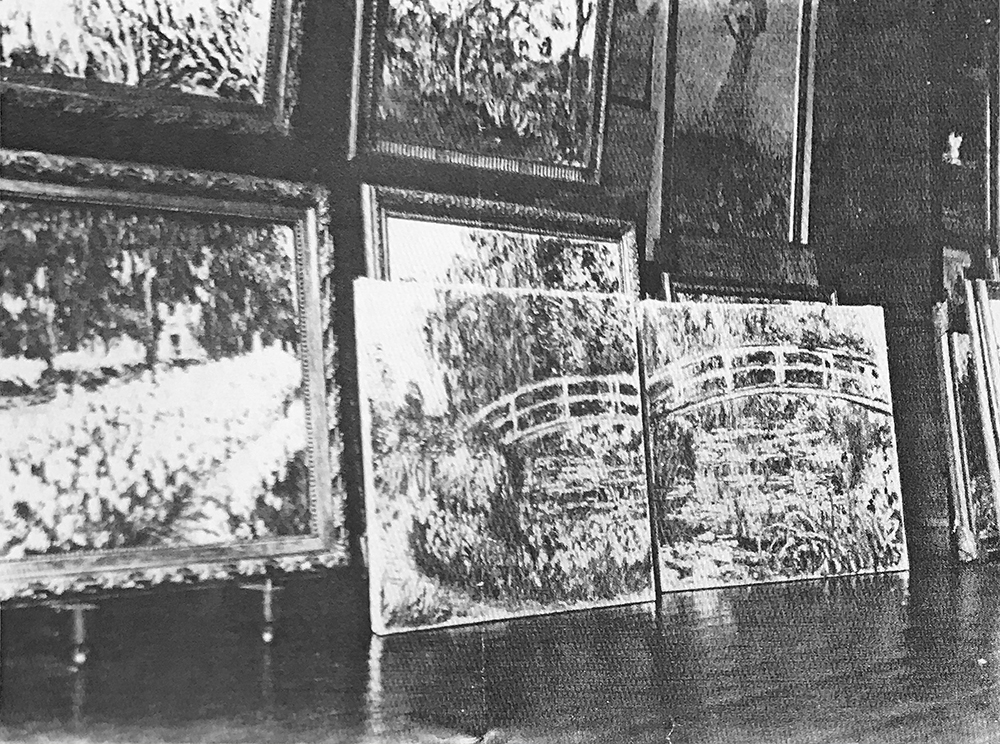

Claude Monet, the studio at Giverny, b-&-w photograph, 1900

Claude Monet, the studio at Giverny, b-&-w photograph, 1900

There is evidence that Monet, for instance, preferred to frame his paintings for exhibition or sale in traditional gilded patterns; some late photographs taken in his studio in September 1900 make this very clear. In the example above, the large painting on the left is Le jardin de l'artiste à Giverny, painted that year and sold two months after the photo was taken; it is now in the Musée d'Orsay, still in its original frame.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Le jardin de l'artiste à Giverny, 1900, 81.6 x 92.6 cm., & detail, Musée d'Orsay

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Le jardin de l'artiste à Giverny, 1900, 81.6 x 92.6 cm., & detail, Musée d'Orsay

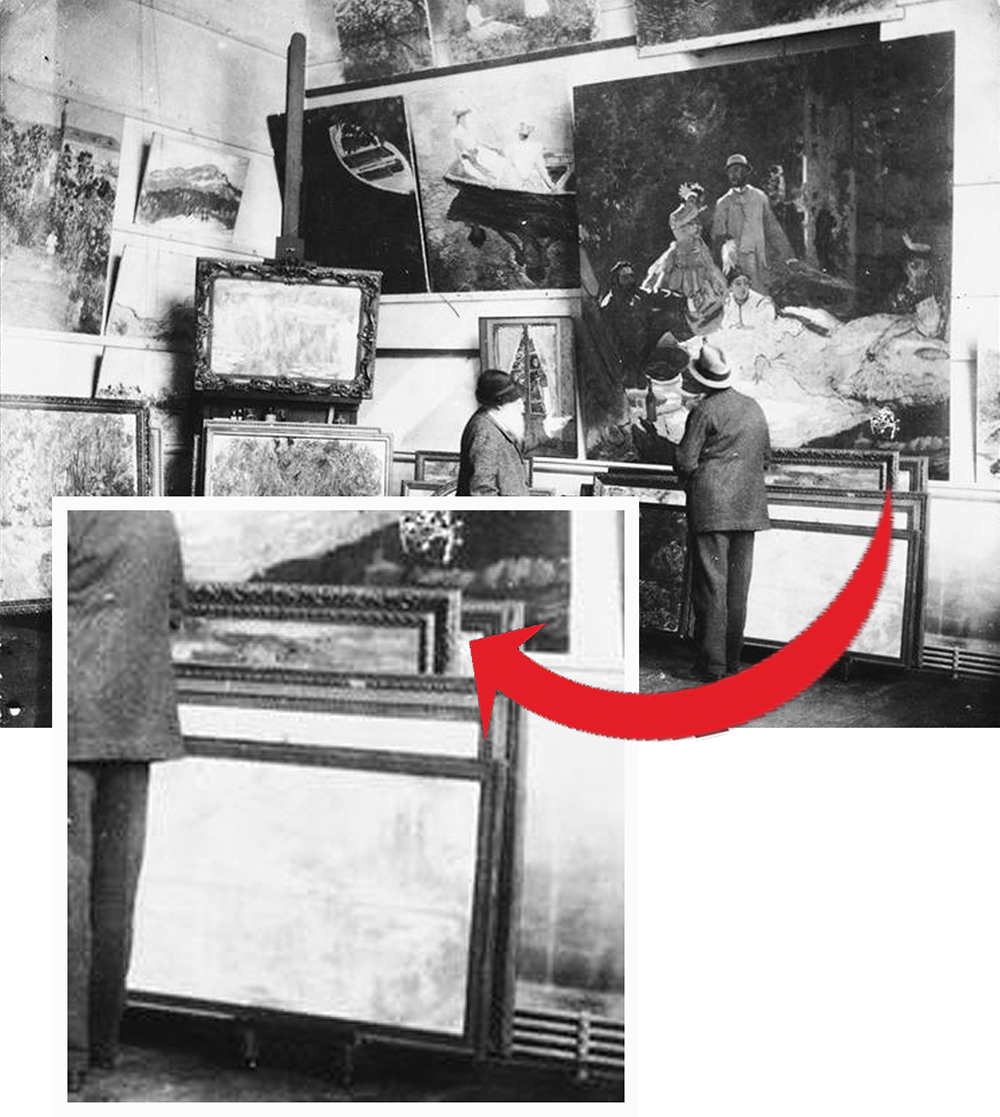

Claude Monet in his studio at Giverny with the Duke of Treviso, b-&-w photograph, 1900

Claude Monet in his studio at Giverny with the Duke of Treviso, b-&-w photograph, 1900

Another photo from 1900 shows Monet himself in a different corner of his studio; here he is showing the Duke of Treviso part of his vast painting, Luncheon on the grass (1865-66, Musée d'Orsay). Behind the Duke, on the right, the tallest canvas emerging from a stack of four (probably a painting of waterlilies) is framed in a torus moulding with bunched fruit-&-foliage decoration. This is a direct revival of a Louis XIII style from the 17th century: possibly even a re-used antique frame, since Renoir, for instance, occasionally used old frames for his work.

Camille Pissarro (1830-93), Boulevard des italiens, morning, sunlight, 1897, o/c, 28 13/16 x 36 1/4 ins, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Camille Pissarro (1830-93), Boulevard des italiens, morning, sunlight, 1897, o/c, 28 13/16 x 36 1/4 ins, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Following the evidence of these photographs, a townscape by Pissarro was placed by Paul Mitchell Ltd in an antique Louis XIII frame, almost identical with that in the photograph of Monet in his studio.

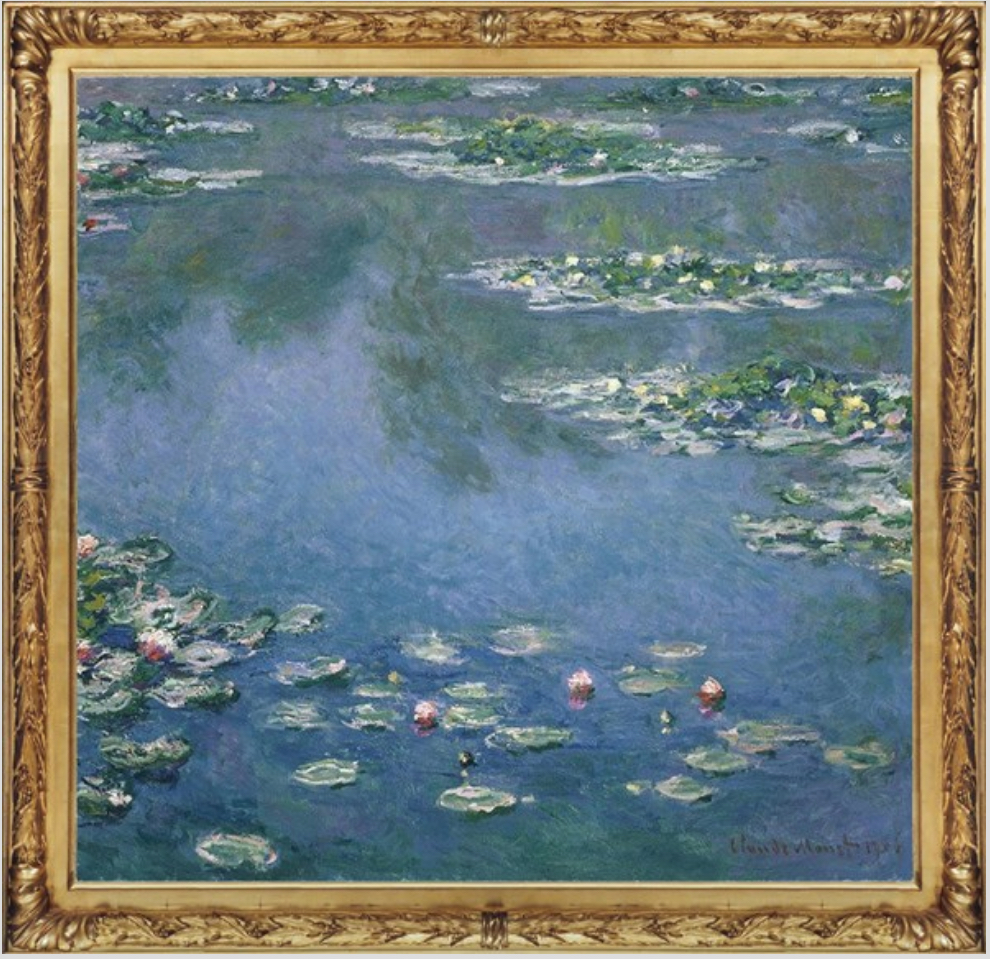

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Waterlilies, o/c, 35 x 36.3 in, private collection

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Waterlilies, o/c, 35 x 36.3 in, private collection

Paul Mitchell Ltd framed another painting of waterlilies by Monet in a foliate torus moulding with plain frieze, similar to the original frame of Le jardin de l'artiste à Giverny; this is a hand-carved replica of a late 19th century Louis XIII revival frame.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Julie Manet (L'enfant au chat), 1887, o/c, 65 x 54 cm., Musée d'Orsay

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Julie Manet (L'enfant au chat), 1887, o/c, 65 x 54 cm., Musée d'Orsay

It echoes further examples of this type of frame in the Musée d'Orsay; for example on Renoir's portrait of Julie Manet, daughter of Manet's brother, Eugène, and his wife, the Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot. Again, this remained in the collection of Julie's family, until it was accepted by the Musée d'Orsay in 1999.

These examples of works by Monet and Renoir, after their early experiments with coloured frames had ceased, reveal that they and their friends and patrons chose to use either conventional 'Salon' frames, or contemporary variants on these; and that to follow their lead will usually result in a more successful relationship of painting and frame than is often true when their work is framed in antique Louis XV and Rococo patterns.